Search

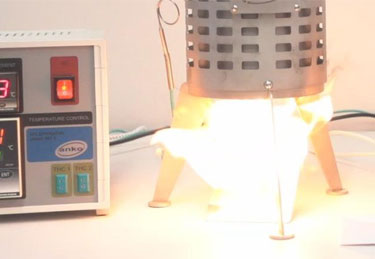

Thermal Instability (Self-Heating) in Spray Dryers

Quality Control approaches you with an issue. They have detected yellowing or even brown specks in the spray-dried milk you are producing. It’s a one off and the operations director suggests you just clean the dryer and carry on. [Incidentally, this story could equally well relate to products such as coffee, eggs, cereal, pharmaceuticals, pigments, microalgae…]

Are you happy? What do you do?

Yes, there could be a bit of contamination somewhere, but milk powder has something in common with many other organic materials – it is thermally unstable at relatively low temperatures and in some circumstances, it can self-heat and even catch fire (self-ignition). A self-heating powder can, of course, lead to a fire and/or dust explosion with all the risks of injury, plant damage, business interruption, loss of confidence etc. that follows.

Powder explosions? What do you do?

Clearly, it’s worth a close inspection of the spray dryer and associated plant – the dryer, cyclone(s), filter units, downstream storage and packaging, and so on. Pay particular attention to the spray jets/rotary atomizer and top walls and roof of the dryer, looking for thicker layers or discolored deposits. Product build-up inside the spray dryers is common, but how thick are the deposits and if it’s a rotary atomizer, is it running free?

In addition, it is worth exploring the thermal stability characteristics of the product. You need to understand that milk powder, in common with other thermally unstable materials, does not have a unique temperature at which self-heating begins. There is no unique onset temperature for self-heating. The thicker the deposit, the lower will be the self-heating onset temperature – and air flow over or through the deposit will affect the onset temperature too. Air can cool but it can also provide oxygen – the lifeblood of thermal oxidation.

Thermal Instability Testing

At Stonehouse laboratories, we have a comprehensive range of tests that can be used to properly evaluate the thermal stability (self-heating) of materials. They can be used to set safe drying and storage/packaging temperatures and can give an indication of how minimum thermal decomposition temperature falls as layers get thicker or powder quantities in storage vessels/containers get bigger. This can be used to give guidance on cleaning frequencies as well as for setting safe drying temperatures – something our consultants do regularly.

So, when Quality Control Department approaches you having detected a degradation of the product you are producing, stop, inspect plant and be sure you have all the appropriate data you need on the material to evaluate what is going on. If it is a thermal instability (self-heating) problem, safe conditions can be determined with knowledge, expertise, experience, and understanding. Be sure you also have all the other data you need (perhaps minimum ignition energy (MIE), explosion severity (Kst), and more) to be sure all ignition sources are covered and also that the explosion protection you have on plant is properly designed to cope with an explosion, if one were to occur. There is also equipment you can get which attempt to pick up the early signs of product degradation by monitoring for carbon monoxide production – a product of the decomposition process. In short – complete your Dust Hazard Analysis (DHA) in accordance with NFPA 652 and ensure all combustible dust fire and explosion prevention and protection measure are identified and in place!

Please contact us for further information on how we can help you run a safer plant.

Get in touch

To learn more about our expertise and services in dust explosion prevention & mitigation, call us at +1 609 455 0001 or email us at [email protected] today.

We also offer tailored virtual and in-company process safety training programs on Dust Explosions, Static Electricity and HAC (Hazardous Area Classification) and more. Find further information here.

We use cookies to help us enhance your experience on our website. By clicking “Accept,” you consent to our use of cookies. Read our Privacy Policy for more.