Moving Dangerous Materials!

- “As the supplier’s truck entered our delivery bay, I noticed there was smoke coming from its cargo space; a disaster waiting to happen.”

- I have a material that could be hazardous. I want to transport ‘a quantity’ of my material to another facility. How should I package and transport it?

Enter the highly regulated world of Transport of Dangerous Goods/ Hazardous Materials (HAZMAT).

In this special article for Process Safety Dispatch, we look at the principles behind the international rules that regulate how you must package dangerous goods for transportation by air, sea, road, rail – and even inland waterway. We also look at a few of our laboratory tests that we perform for clients to help them make their packaging and transportation decisions.

But firstly, let’s look at what can happen. A few years ago, there was a manufacturer of a detergent powder. They changed their packaging for transport, increasing size. Before long, one of their batches self-ignited, just as it was being delivered in bulk by truck to their customer.

Materials can self-heat through spontaneous decomposition (e.g., fibers, carbon or activated carbon); they may just need the oxygen in the air to start self-heating. Materials may promote oxidation of other materials (oxidizers – e.g., sodium chlorate, peroxides…). Some materials, be they liquids or solids, could also simply be flammable (e.g., ethanol, kerosene, hay or straw, sulfur). Materials with these various hazard properties are surprisingly common and include everything from the most exotic chemical formulations through to everyday materials you routinely find at home. But let’s look at your material.

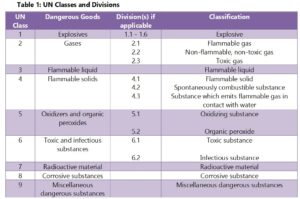

Classes of Dangerous Goods

For your material, the first question you’ll want to have answered concerns the danger it could present. In the language of United Nations Model Regulations [ref 1], you’ll want to know if your material is classified as Dangerous Goods – also known as “hazardous materials” or “HAZMAT” in the United States. In fact, the UN has identified 9 Classes of Dangerous Goods, each with its own UN Class number. Our table 1 lists these 9 Classes. The list includes ‘explosives’, ‘flammable gases’, ’flammable liquids’, ‘flammable solids’, ‘oxidizers’, ‘organic peroxides’ and more. But if you look more closely at the table, you’ll also notice subdivisions of some of these categories that allow for a little more granularity to the hazard classification. Some of the hazard Classes are subdivided into Divisions that allow for different material properties within each Class. So, for example, we see that flammable substances are divided into ‘Flammable Solid’, ‘Spontaneously Combustible’ and ‘substance which emits flammable gas when in contact with water’. The need to subdivide in this way is clear if we think about the precautions we need to take if we are to safely transport a flammable solid that will catch fire with an external ignition, one that will self-heat with no external ignition source or one which will liberate a flammable gas if in contact with water! So, this naturally leads onto the need for different Packaging Groups – PG I, PG II, or PG III, appropriate for the different hazards posed. The packing group determines the type/ degree of protective packaging required.

Data, Data, Data

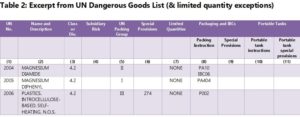

To establish if the material you wish to transport is classified as Dangerous Goods/ Hazmat, it’s possible that you’ll need to have it tested by an experienced, quality-assured laboratory such as ours at Stonehouse. The UN publish lists of Dangerous Goods, and this is always the starting point in establishing how you might pack and transport your materials. The list also contains exceptions for some materials if you only want to transport a limited weight or volume. Although the UN published list is an essential first point of call, you must also be aware that any differences between your material and those listed might affect its hazard properties, which is a reason why you may still have to subject your material to testing. Small contaminants or even particle size differences can sometimes make a big different to hazard properties.

We’ve shown an extract from the UN Dangerous Goods List in our table 2 below, simply as an example of the data available to assist with transport and packaging decisions if your material has already been classified as dangerous goods/ HAZMAT.

Testing

For as yet unclassified materials, the UN has published very precise laboratory test methods that must be used by labs such as Stonehouse for the classification of dangerous goods and for their assignment to packaging groups [ref 2]. At Stonehouse we specialise in measuring physico-chemical properties of materials, and we therefore select out illustrative Flammable Solids tests by way of example.

Class 4, Division 4.1: Flammable Solids

In order to differentiate between substances that can be ignited and those which burn rapidly, or whose burning behaviour is particularly dangerous, only substances whose burning rate exceeds a certain limiting value are classified in Division 4.1.

We use a line or train of powder material, prepared from a 250mm long mould, ignite one end using an ignition source of particular design/ energy then measure the time taken for the flame to transit 200mm down the line. We’re looking for flame transit times of less than 2 minutes, 2 to 20 minutes or more than 20 minutes to start the classification process. A powder that allows flame to transit the length of the powder train in over 20 minutes is classified as ‘a Not Readily Combustible solid of Division 4.1’. For faster burn transit times, we may then go on to introduce wetted zones to the powder train. The results allow us to specify Packaging Groups for the powder, therefore, as either Division 4.1 PG II or Division 4.1 PG III.

Of course, environmental and material parameters need to be carefully controlled and rigorous scientific method followed to allow us to make a material classification.

Class 4, Division 4.2: Substances liable to spontaneous combustion

The test procedures in this category are intended to identify two types of substances with spontaneous combustion properties:

- Those liable to spontaneous combustion – pyrophoric substances – which ignite within five minutes of coming in contact with air.

- Those which, in contact with air and without an energy supply, are liable to self-heating. Substances that will ignite only when in large amounts (kilograms) and after long periods of time (hours or days) are referred to as self-heating substances.

Tests for pyrophoric substances is different for liquids and solids, with the former being added to an inert carrier substance for the testing. Essentially, a material is classified as a pyrophoric substance of Division 4.2 if it ignites within five minutes of coming in contact with air.

Division 4.2 also encompasses self-heating substances, such as the one described in the opening remarks of this article. The test for self-heating substances makes use of a solids placed inside wire baskets of 100mm or 25mm side length. The sample is placed in a temperature-controlled environment/oven and held at 100degC, 120degC, or 140degC and thermocouples used to monitor oven and sample temperatures. Packaging Groups II and III are assigned to the Division 4.2 substance, based on evidence of self-heating in the result of these tests.

Class 4, Division 4.3: Substances which emit flammable gas in contact with water

Testing here revolves around wetting the substance and (a) looking for evidence of gas generation, then secondarily, looking to see if evolved gas can be ignited. Packaging group I, II, and III are then allocated to the substance based on the rate of flammable gas evolution.

Summary

The source of most national regulations detailing how dangerous goods/ hazardous materials are moved by almost all modes of transport is the UN Orange Book. The Orange Book groups transport hazards posed by these materials into nine classes, which may be subdivided into divisions and/or packing groups. The packing group determines the degree of protective packaging required.

Many materials have already been classified and if your material is included in UN lists you may not need to have it tested but remember that small differences, contaminants or even particle size can sometimes make a big different to hazard properties. Some generically classified materials may still need to be tested!

If you are unsure about material classification or transport or if you require lab testing for purposes of transportation, please enquire via our contact us website page, email: info@stonehousesafety.com or call 609-455-0001.

Epilogue

The UN Orange Book means the UN Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods Model Regulations, a guidance document developed by the United Nations to harmonize dangerous goods transport regulations. Most of dangerous goods regulations such as IMDG Code, IATA and other national regulations are developed based on the UN Orange Book

Each day, U.S. businesses transport over one million ‘dangerous goods’ (‘Hazardous Materials’) shipments, and every one of them is subject to US Department of Transport (DOT) standards. The regulations establish standards for HAZMAT identification, training, labelling, use of proper containers, recordkeeping, reporting, placarding, and vehicle safety.

The basis of DOT standards is The UN Orange Book, which itself is not a regulation. However, like the US, many countries have adopted the UN’s Model Regulations and take basic provisions from the Orange Book and implement them in their own dangerous goods regulations or standards depending on the mode of transport.

References

- UN Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods – Model Regulations – United Nations, New York and Geneva https://unece.org/about-recommendations

- Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods – Manual of Tests and Criteria – United Nations, New York and Geneva